How to Think about Coronavirus Like a Public Health Expert

Patricia Wren, MPH ’92

Professor and Chair, Department of Health and Human Services, University of Michigan-Dearborn

Click Here for the Latest on COVID-19 from Michigan Public Health ExpertsIf there was a single theme that defined the coronavirus pandemic response over the past week, it might be that we’re all starting to see the world the way public health experts do. Terms like “social distancing,” “pandemic,” and “flattening the curve” have become part of our everyday vocabularies. Social media is filled with examples of friends pleading with each other to stay home and “shelter in place” rather than go on with business as usual. To keep nurturing those burgeoning public health instincts, we hear now from Patricia Wren—public health professor and chair of the University of Michigan-Dearborn’s Department of Health and Human Services—to share how she’s thinking about our collective response to the pandemic. Here’s the conversation, which has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

One of the big developments of the past week was witnessing leaders—and the public—start to take this really seriously. Still, many people see measures like closing restaurants and bars as extreme. From a public health perspective, make the case that these kinds of disruptions to our lives are worth it.

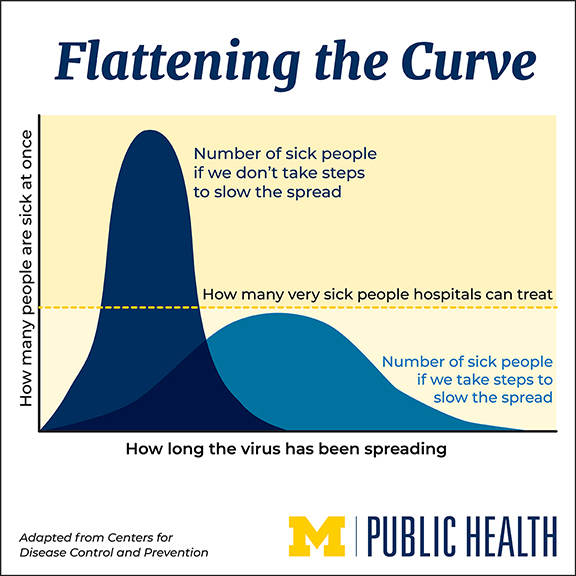

Patricia Wren. The way I’m thinking about this is that we have an opportunity right now to learn from the experiences of other nations. The data showing the rates at which this pandemic took off in China, South Korea, Iran, and Italy are really compelling. In all those cases, when you look at the charts showing the spread of the disease, you see the line just shoot up like a rocket ship. We’re about two weeks behind all of those other rocket ships that launched. So we have to take dramatic action, like social distancing, to slow the movement of the virus through the population. That’s what we call “flattening the curve.”

If we do that, we’ll maybe have a longer experience of whatever this crisis is. But without it, we overwhelm our grocery stores, our families, and our health care system—which we certainly don’t want to do. So that’s why it’s really essential that all of us take these steps now, so that in a country like the United States, which is five times larger than Italy, we don’t experience five times the number of cases and deaths. I think that’s the kind of scale we have to keep front of mind.

You mention that successfully flattening the curve means we likely will extend our experience of the crisis, living with social distancing and mass cancellations of programs and events for a long period of time. Should we really be thinking about this kind of collective response to the pandemic lasting through the summer?

Wren. If you look at the messaging from University of Michigan officials—and we are just one large institution of many that are dealing with this—we are getting some clear signals. We already have indications that summer classes are going to be offered via online platforms. Fall is still a good six months away, but we are talking about online classes being an appropriate measure for at least the next six months.

The size and scale of the impact is not yet quantifiable. But we certainly do need to imagine how this could continue into the fall and plan accordingly.

These changes are a really big deal, and we have to begin to wrap our minds around what our neighbors are going to need, what restaurant workers are going to need, the impact on small businesses, what our students—whose families’ livelihoods are at risk—are going to need. I think the size and scale of the impact is not yet quantifiable. But we certainly do need to imagine how this could continue into the fall and plan accordingly.

We’ve seen the threshold for “social distancing” evolve rapidly in the last week. As of today, the best practice seems to be limiting any kind of unnecessary contact with other people, even in small groups. How do we draw the line between what’s necessary and what’s risky?

Wren. One thing we know about human nature is that we aren’t especially good at assessing risk. This is especially the case when we’re confronted with risks that feel amorphous or vague. In my intro to public health class, I teach this to students by talking about the risk of driving to class. Statistically, that’s the single biggest risk they could take, because for people their age, motor vehicle crashes are the leading cause of death. And yet we don't think anything of jumping in the car to go to class or work or meet with friends.

So now, we have this crazy pathogen thrown into the mix, and we’re having trouble sorting out what social distancing really means and how much we really need to restrict our comings and goings. At this point, thinking about ways you can shelter in place and be more homebound is absolutely a good thing. Because people can have the virus for days before they experience symptoms, it’s not enough to avoid going out when you have symptoms—you have a cough or fatigue or fever or shortness of breath. Can you play in your yard, take a walk, walk the dog? You bet. But you have to be much more mindful of so many details. I find myself constantly thinking about the elevator button or door handle I just touched that other people have touched. Even things like gatherings or getting family togethers are things we should think about doing without for a while, because we have to be so much more cautious given the way this virus spreads

So let’s say you have friends or loved ones who aren’t moving in that direction and are continuing more or less like it’s business as usual. How do you get through to them?

Wren. One of the things we know about public health is that fear arousal has a short shelf life. The whole “this is your brain on drugs” or “you’re going to die if you have unprotected sex”— turns out these worst-case scenarios and fear-based messages are easier to tune out because many of us perceive them as something that won’t apply to us. Fear, as a strategy, isn’t sustaining.

We all have an opportunity to offer corrective advice, to challenge people on social media, to say with love to family members, “I need you to be cautious.

So we have to think about how we do this with love. I think about my students, many of whom are first-generation college students. That makes them touchstones for their families because their families have expectations that these young people will be more knowledgeable than them. So I’m telling my students they have a responsibility and opportunity to be good role models. And we all have an opportunity to offer corrective advice, to challenge people on social media, to say with love to family members, “I need you to be cautious because I want you to be around to dance at my wedding.” I think there are ways we can offer these expressions with love that are tailored to the people with whom we have some influence. That’s far more effective than fear. We also have to be willing to repeat those things multiple times, in multiple ways, until the message gets through.

Are you seeing evidence that the public at large is getting the message?

Wren. I live in Midtown Detroit, and I walk the dog every night. It was pretty wild to see all the bars and restaurants go dark after the governor made her announcement that she was temporarily closing these businesses. It was striking to see how quiet the streets were. That does suggest that even at great financial peril, our state is coming together, our communities are coming together. We’re doing the right thing, as best we know today, to limit the impact of this pandemic.

And finally, are you seeing anything positive in everything that is happening?

Wren. I think the response to coronavirus is teaching us that we are connected in ways we have not conceived of in a while. Our health, our mental health, and our economic health are entirely interdependent. Parallel to that, the other positive I see is that we can take steps to be protective of each other. We of course need to practice good social distancing, but we are learning again what it means to be good neighbors and good family members and have increased patience and resilience and tolerance for each other. I'm hopeful that those are some lessons we as a people—as a nation—might learn again.

About the Author

Patricia A. Wren is professor and chair of the Department of Health and Human Services at the University of Michigan-Dearborn. Herself a first-generation college student, Dr. Wren began her college education at a community college and went on to earn a bachelor’s degree in political science and a master’s degree in the management of public services from DePaul University in Chicago. She also earned a Master of Public Health degree in Health Behavior and Health Education from the University of Michigan School of Public Health and a PhD in education from the University of Michigan. Her research centers on the measurement of patient-centered outcomes—ensuring that decisions about disease progression or treatment success take into account patient preferences and important indicators like quality of life, patient satisfaction, mobility, and functional status.

- Interested in public health? Learn more today.

- Read more articles by Health Behavior and Health Education faculty, students, staff, and alumni.

- Support research at Michigan Public Health.

Tags

- Alumni

- Epidemiology

- Faculty

- Health Behavior and Health Education

- MPH

- Detroit

- Engaged Learning

- Epidemic

- Epidemiology

- First Generation Students

- Health Behavior and Health Education

- Health Care Policy

- Health Communication

- Infectious Disease

- Leadership

- Social Epidemiology

- Teaching

- What Is Public Health?